Projects for Artist Notes:

Recipes for the Open

As a mother to a non-speaking autistic person who types to communicate and who I support in relation to type (he writes poetry, books, journal articles…), I am often asked for a method to teach supportive typing (also called facilitated communication or assistive communication). I find that providing support as a methodology is difficult because it tends to be deductive, and support is about relation, not about reductive steps for relation. It is, rather, always a-stepping. The way Adam, my son, and I have come to think of relation is open; an always moving and shifting relation. When our relation is parsed in the dis/abled scheme - as the teacher and learner - I become falsely viewed as the able-bodied speaker and my son, the disabled non-speaker; my role in this framework becomes hierarchical and rehabilitative rather than mutual and collaborative. Instead, our work together envisions the transience of bodies as the process of relation, not as fixed or separate. As Adam is never the same each day, so too the environment, situation, my body, also changes from day to day. We become with the environment and with each other: an ecological body. Adam writes extensively on the incorporeal - the non-human, invisible world of affective relation, where objects and environment provide just as much a support (if not more than human support) - a way of proprioceptive aligning within it. In our relationship with each other and the world, we attend (a word co-opted by behaviorism) with rhythms, feelings, ways of moving-aligning. Adam refers to this as pace which remains central to thinking about transitions as movement; the intervals and durations consist of the “unfiltered detail” that is not otherwise subtracted from autistic perception. These thresholds, particularly when “fast-paced like talkers” move, can become difficult to navigate, provoking anxiety particularly when the expectation is to move and speak quickly. It is akin to how we think of a world that is architected for the able body; a body preferred for capital (efficient) production. This mode of production and of being, thinks of value as that which can extract or subtract the excess. The autistic body has been imagined within a pathology paradigm as excessive.

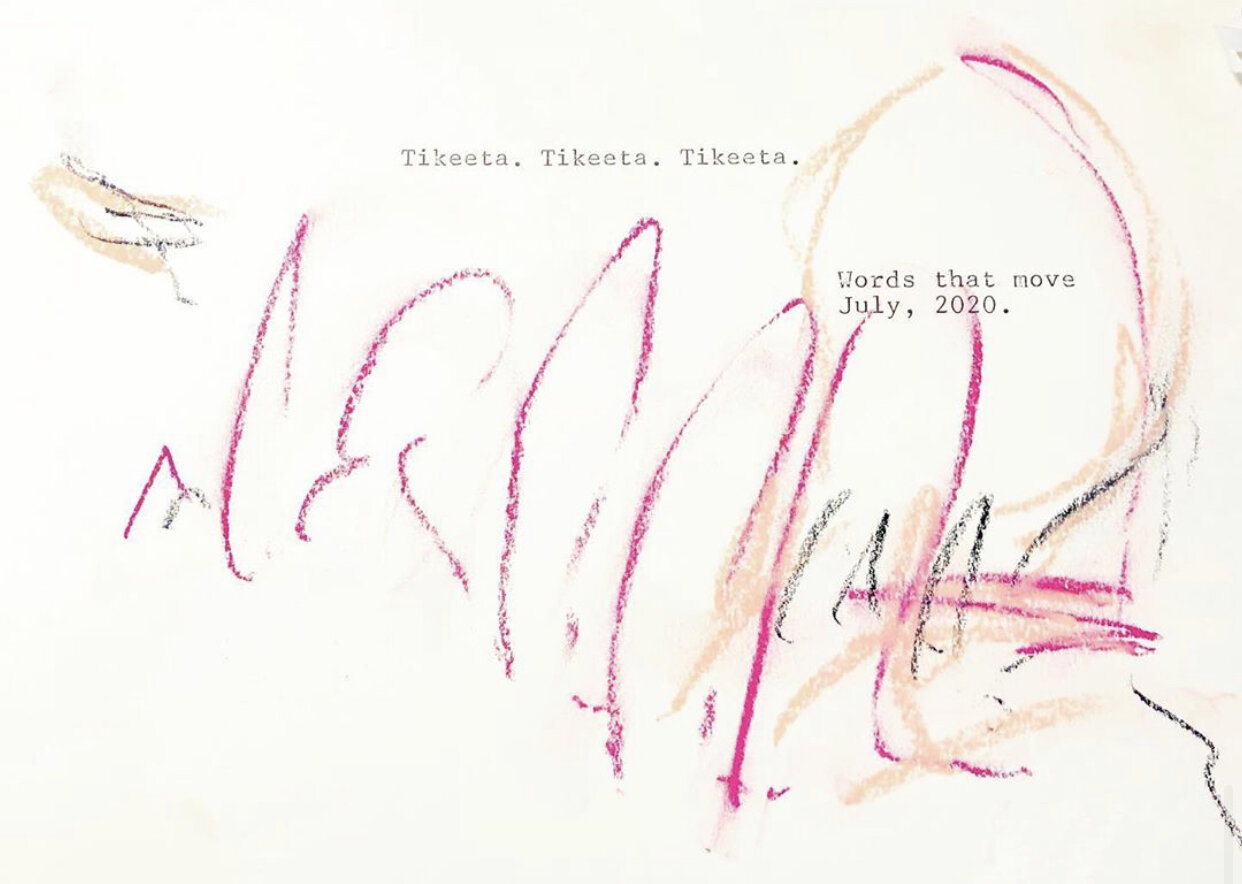

Adam writes much about an attunement to the “background” which is also the foreground of every movement-moment - “in my face” all the time, he writes. He cannot excise the excess but rather lives within it, perhaps a neurotypical lack. He has accustomed himself to facing differently, peripherally, with toy tapping, pattering to pattern pace - to cope in a fast-paced, neoliberal world. Pace is, therefore, never exclusive to two bodies (the duo, the “inter”, often centres on the human relation as separate from the ecology), but is in relation with various pulses, resonances, vibrating objects that are both visible and invisible, and above all, felt. We name this the intrarelation to think about all that move with us - which our otherwise neurotypical culture envisions as pathological, useless, valueless, disordered. We have adopted the term attunement rather than attention (that strict, behaviorist word that invokes how attention ought to be demonstrated) to think about these forces and intensities that move us for a way to think about not only the how of autism, but the how of relation.

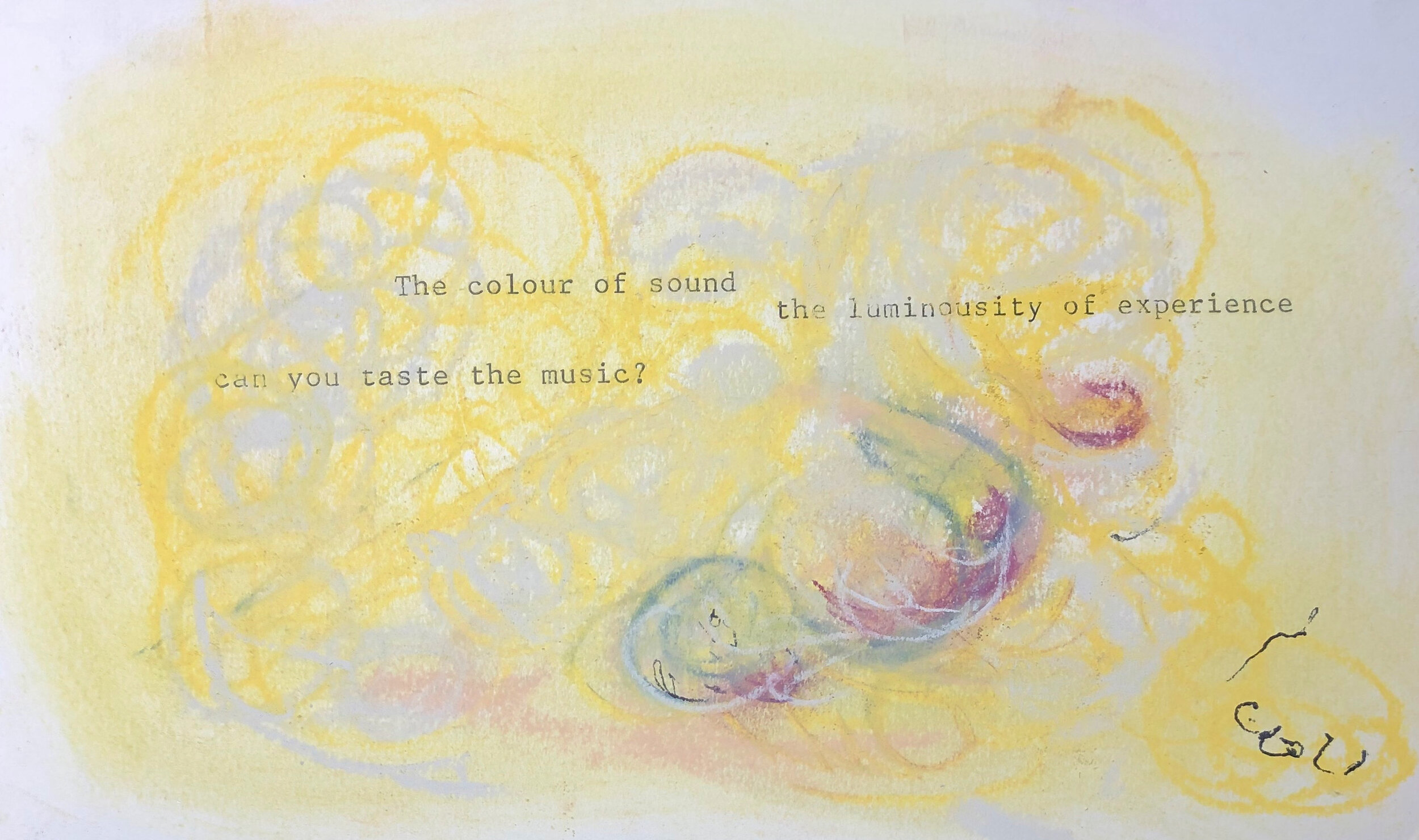

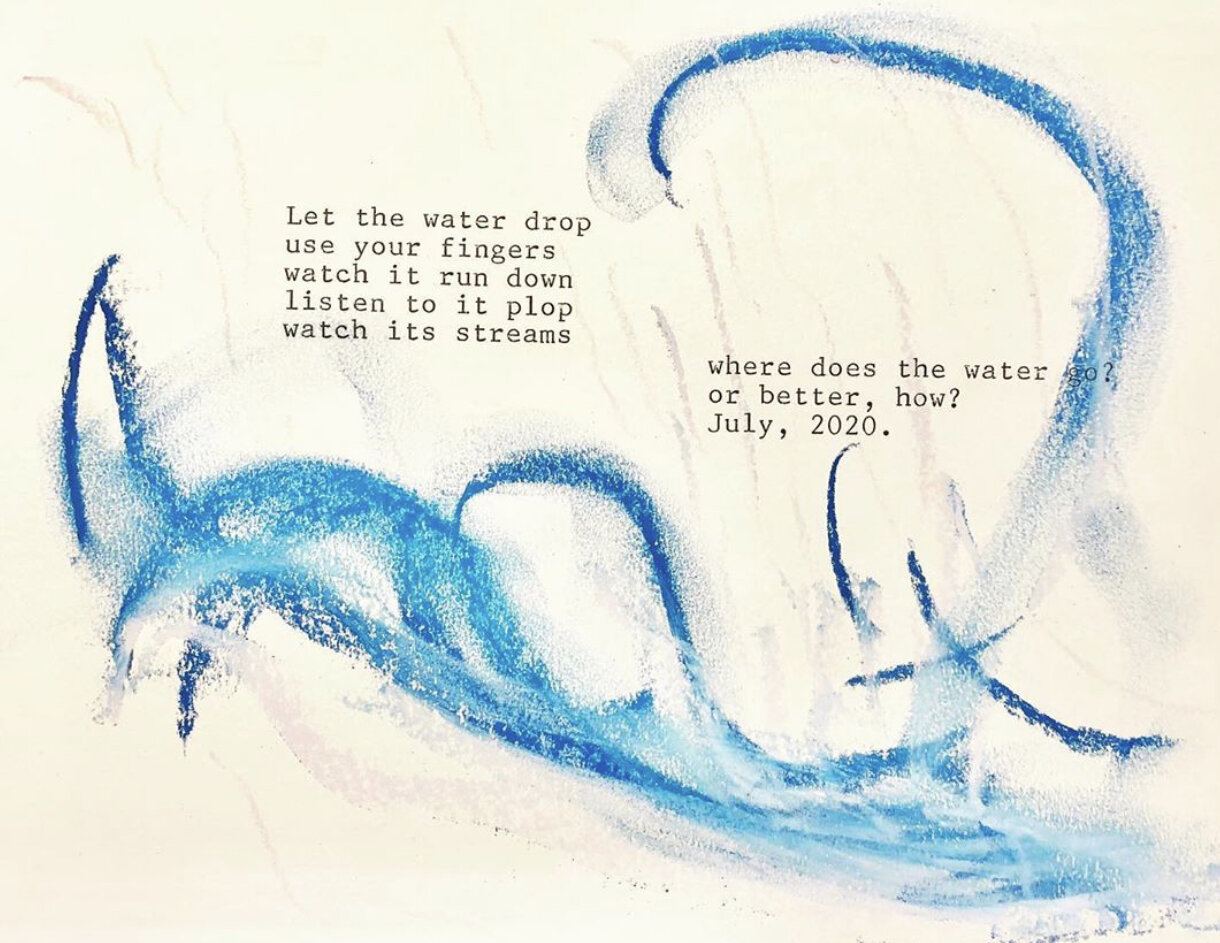

During the writing of my dissertation, someone suggested I write “recipes.” This is asked of me all the time, and any of Adam’s other support assistants and teachers will tell you that we spend several months together before we even begin the supported typing, because bodies need to become accustomed to the nuances of movement. Bodies need to understand bodies through movement. My resistance to writing the step-by-step instruction manual is based on the premise that supportive/facilitative communication is much more than method; it israther, a way of movement that thinks beyond the instructional steps. Rather, it is like thinking about how dancing moves us. We are bodies dancing collaboratively in the complex field of relation. This is not to say that supportive typing cannot be taught - indeed there are good teachers for it - but most of which is actually taught is this understanding of motor planning differences, idiosyncratic movement, autism as perceptual and movement diversity, and above all, an understanding of autism outside the pathology paradigm. I need to add also that people who type to communicate are more than “spellers” (a term I’ve seen recently adopted), but express the texture of relation. This might be expressed as a synaesthetic relation with language (synaesthesia, simply put, is a merging of the senses like hearing colour - but this is still far too simple). I feel this needs to be said because the way autistics come to language is different than the utilitarian use of it. This way of expression elides the objective/subjective narrative but instead immerses in language as movement coming to expression. Rather than pointing and requesting, Adam could read before he could stand up; he simply delighted in words - beyond their utility - recently writing that “words vibrate colours and sounds.” I’d never before witnessed someone come to language on his own before he could walk, as he hoisted himself up on the side of his playpen to read the titles of bookspines on the adjacent shelf (he can speak words). Later, the way he learned to type became rich in associations and gerunds - what he calls “verbing”. Language to Adam is everything as a languaging that moves. As such, we merge poetic and artistic/movement practices such as walking and working with water - a theme Adam is presently working on for his own book.

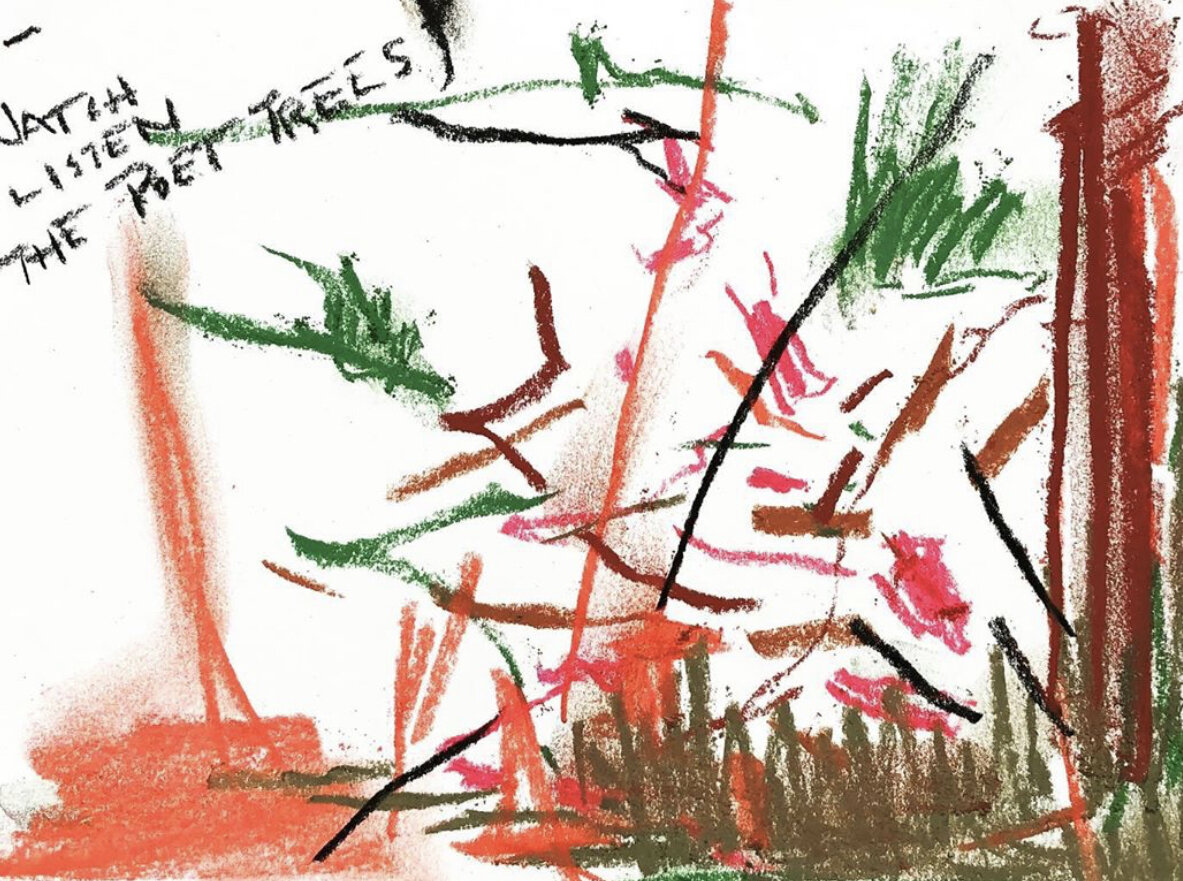

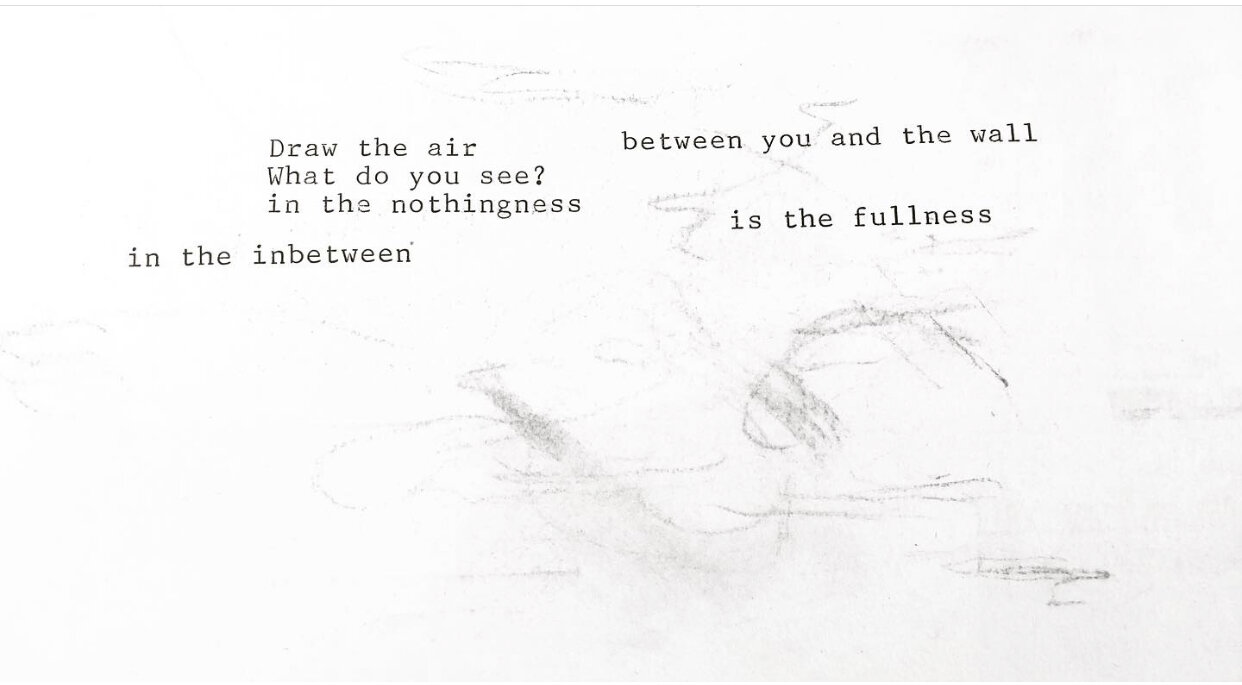

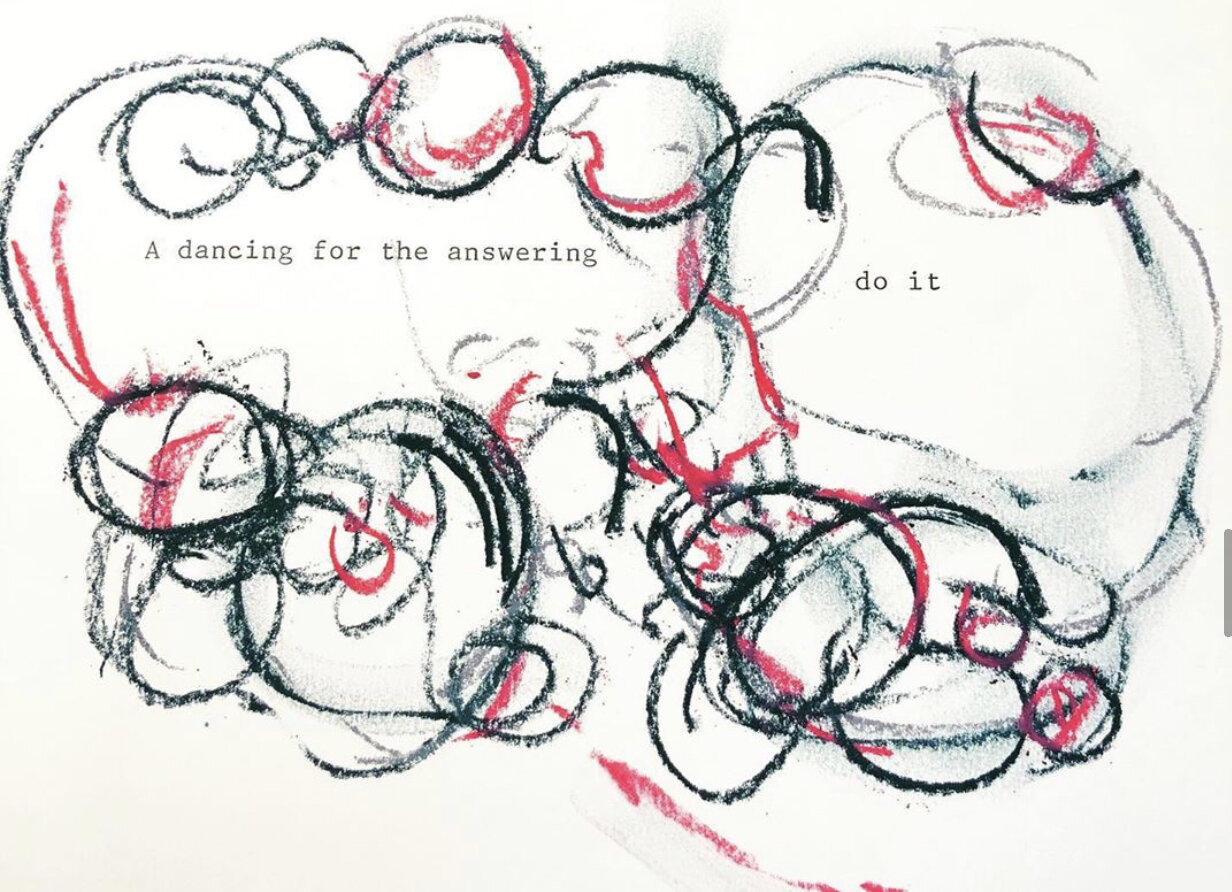

Typing, telling, narrating is a subtractive exercise - so difficult to excise that which moves neurodiverse perception! Non-speaking typers like Adam grasp-toward-through (see: Manning, 2020) that I have come to think of the way Adam not only writes sentences, but moves, and sometimes struggles through transitions. We think of every movement as transitory so therefore moving from one point to the next, including moving a limb, is difficult. This is the essence, also, of support; an attunement to these differences, this registering of all within the transition all at once. Adam recently wrote that everything is always moving, echoed from an earlier poem he wrote “The Walls Are Never Still” (2019). It is as much our focus and interest as his struggle to bring back to the field these otherwise excluded, excised movements from expression such as writing and art. Once trained to excise the affective, to communicate effectively and efficiently, all that is part of experience can be lost. It can take years for writers to regain what comes to Adam naturally (I use words of “nature” cautiously). When we subtract the excess, we also subtract all that constitutes relation, and artistic processes seek to regain and express these experiences which cannot always be written down. In the neoliberal scheme, relation becomes a manufactured, utilitarian concept of how we are supposed to act and express within particular environments, and as we see, “professionalized” interactions fear litigation and so parse the relation even more (think doctor/patient relations and you have it). Neurotypicality parses relation and puts the human and language above all life - the top of the chain - marking human life as intelligent, agential, independent. Language is therefore not only instrumentalized, but weaponized against beings who express otherwise, who don’t make rational sense of sense. Attunement, however, pays attention to the the ever-shifting nanoseconds of movement, “calls” that dance our bodies; a dance vital not only for survival, but for thriving in an otherwise ableist world that excludes excessive, exuberant, moving…autistic bodies. As suggested, Adam articulates this movement as “answering the calls” within the space, to other moving bodies, be they human or non-human. In effect, this is the more than human to which we attune.

In the dissertation, I write that Adam has influenced my way of thinking and also writing. It must be written how autistic people like Adam have shaped us and our ways of thinking and expressing. Little is written by the one perceived as the “facilitator” of the way the autistic person shifts the way we think, write, support. This is a mutual collaboration perhaps made more evident because Adam is autistic and the idea that he can influence me is perhaps a new concept (the onus is typically on the autistic to prove their independence from their facilitator). We suggest that collaboration happens all the time and that the independent (able) artist, author, inventor is the myth of neoliberalism, and also, of the “mastery” that has come to infiltrate the art world. This way of thinking manifests in the arrangement of neurotypicality - an arrangement that tells us how to move, to think, walk, behave, sit still, talk, be… and express ourselves as sole arbiters/authors/makers. This thinking linear, developmental, methodological - and wants easy-to-use recipes. It wants Adam to write about his autistic experience in the language of neurotypicality and its forms while he has otherwise insisted: “I don’t want to answer stupid questions about autism […] I want to move to express myself.” Perhaps the “stupidity” of the questions wrests in the whys of autism - and not the deeper questions about diverse experience - the hows.

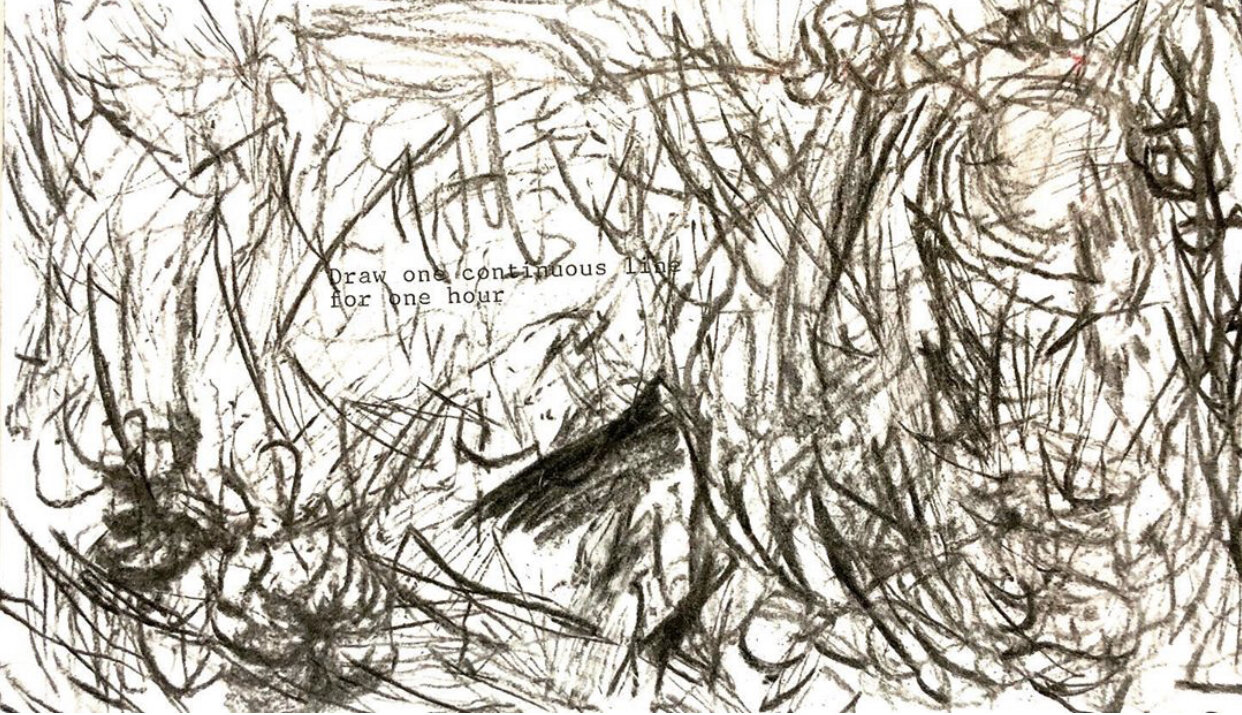

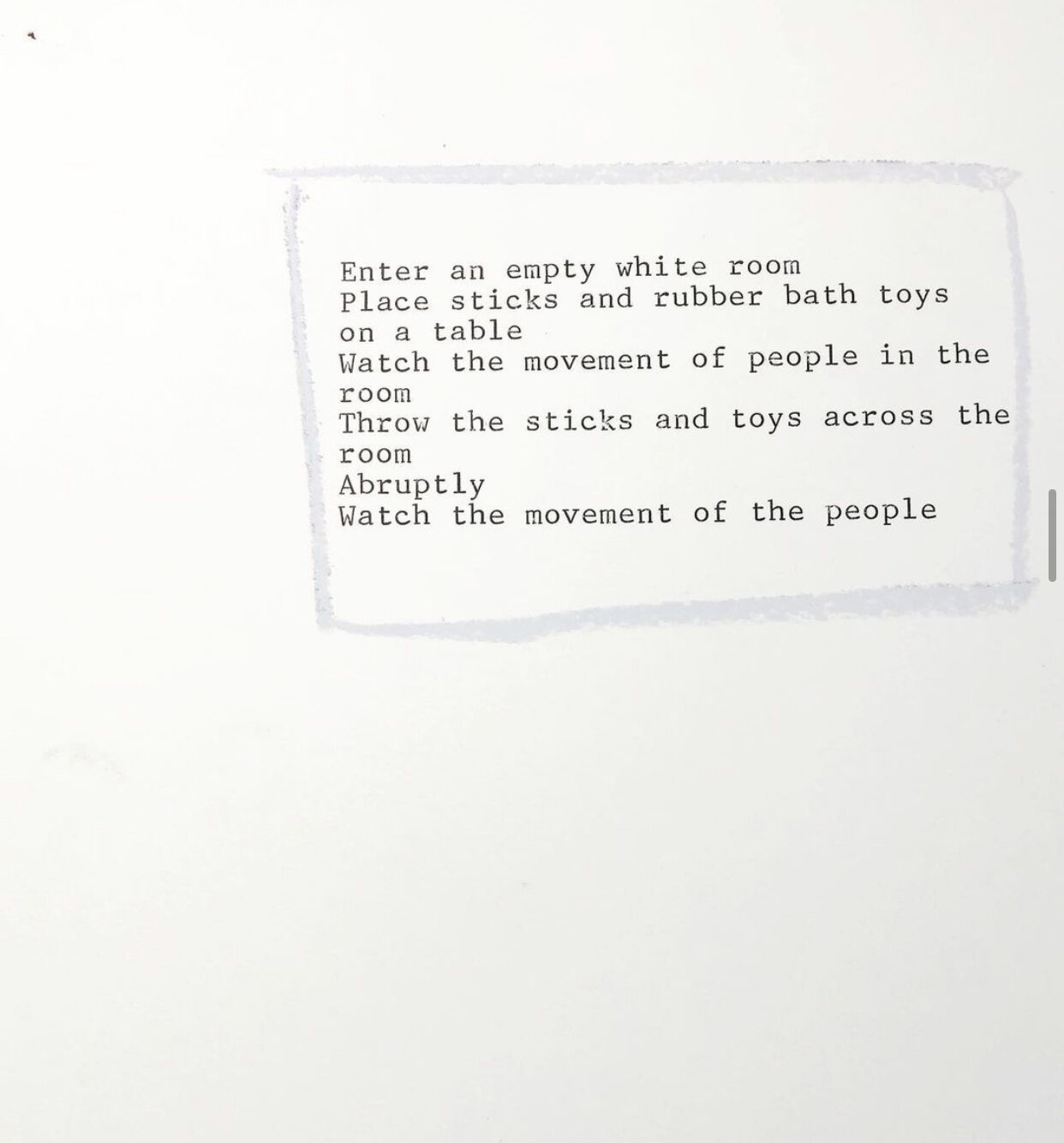

Adam writes, “art is the open way of telling.” Opening is the theme of his work - as wayfaring wanderlines that - when we think, work, play, repeat and attend to them - become a plane of consistency that emerges from the disassembling of narrative, rationality, and other nefarious acts intelligence. This is not working with a pre-planned goal to make art. Art is the open, processual movement with materials, walking with the world. These recipes for the open emerge post-dissertation, post-PhD defense, and after my mother suddenly passed away from cancer. One of the first things I took away from her apartment was her recipe box. She had not only collected recipes that left holes and gaps in the instructions - that allowed for improvisation - but also notes, pieces of drawings that she saved from when I was a child. What can the end result of a cake be when there is a timing instruction or an ingredient piece missing? What can I recall of how it should be and how does my memory move in the act of making? What about shift in temperature, the make of the oven, the difference of pressure and velocity of a spoon stirring in a vat of dough? All of these moments, movements, durations, intensities can render a different result each time. My mother’s little box of recipes contained not the step-by-step guide for living and making, but - whether she knew it or not - the open suggestions for it; for experimentation. A box full of memories never the same twice.

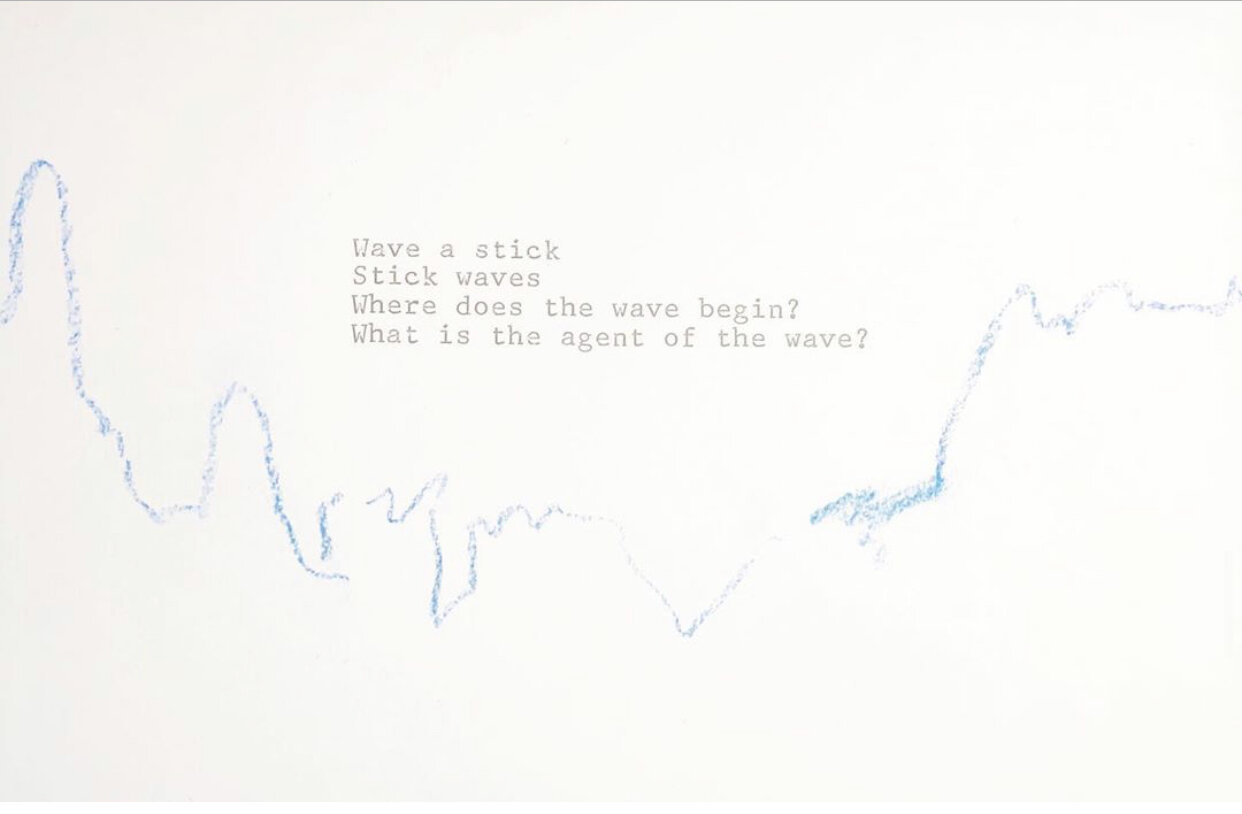

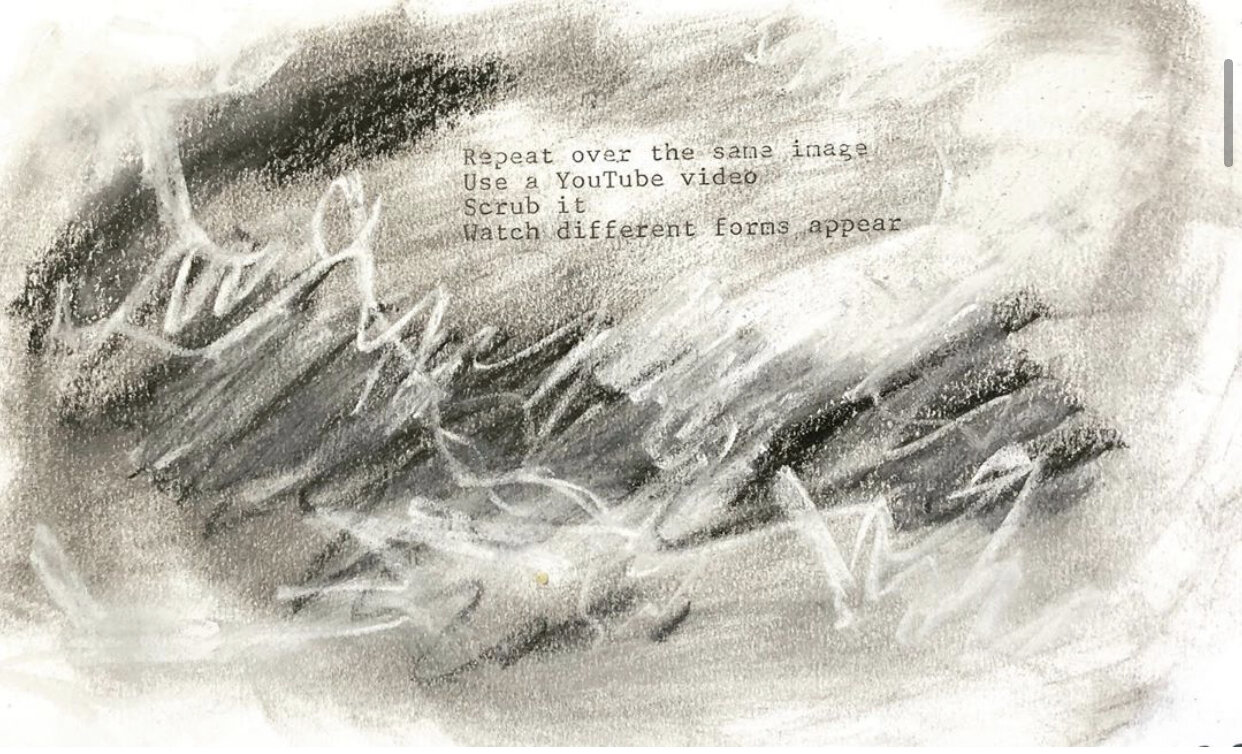

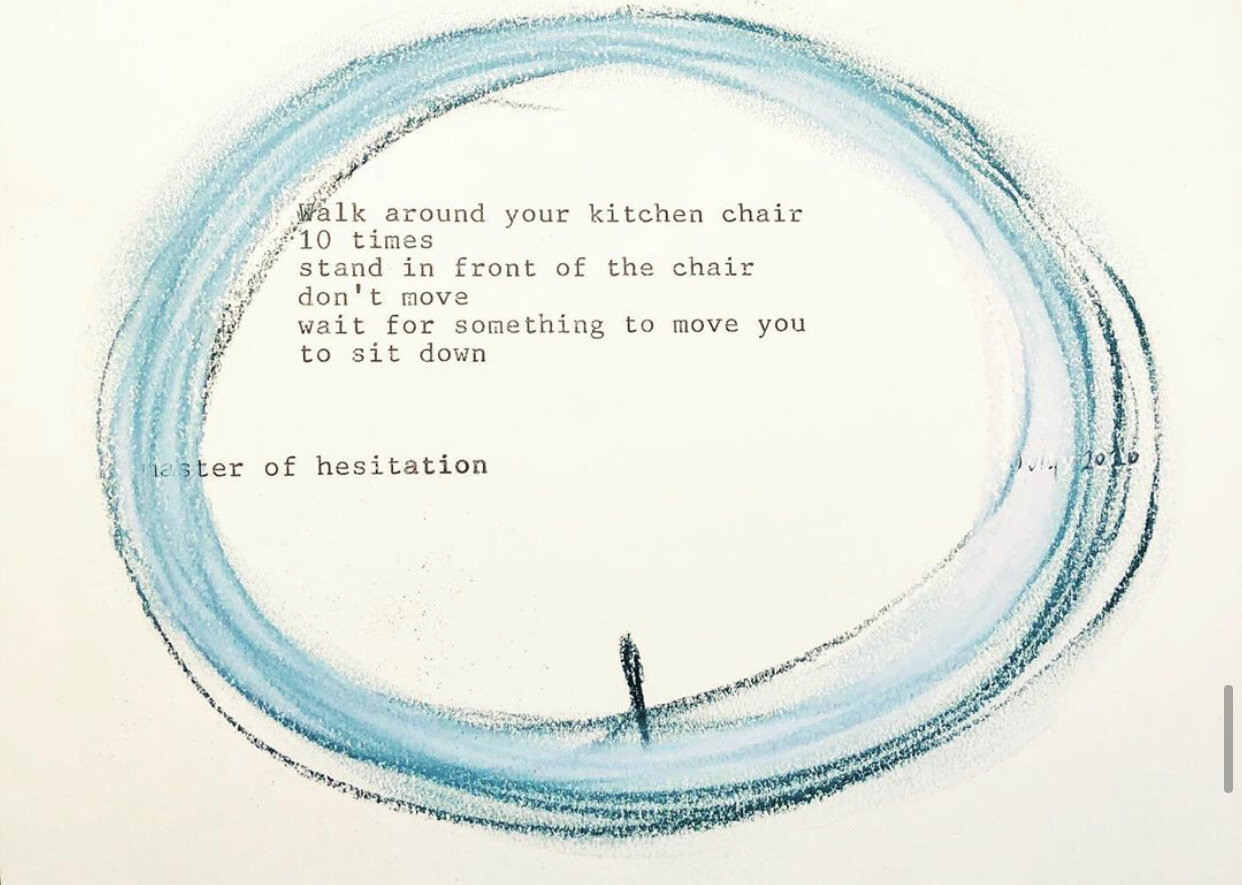

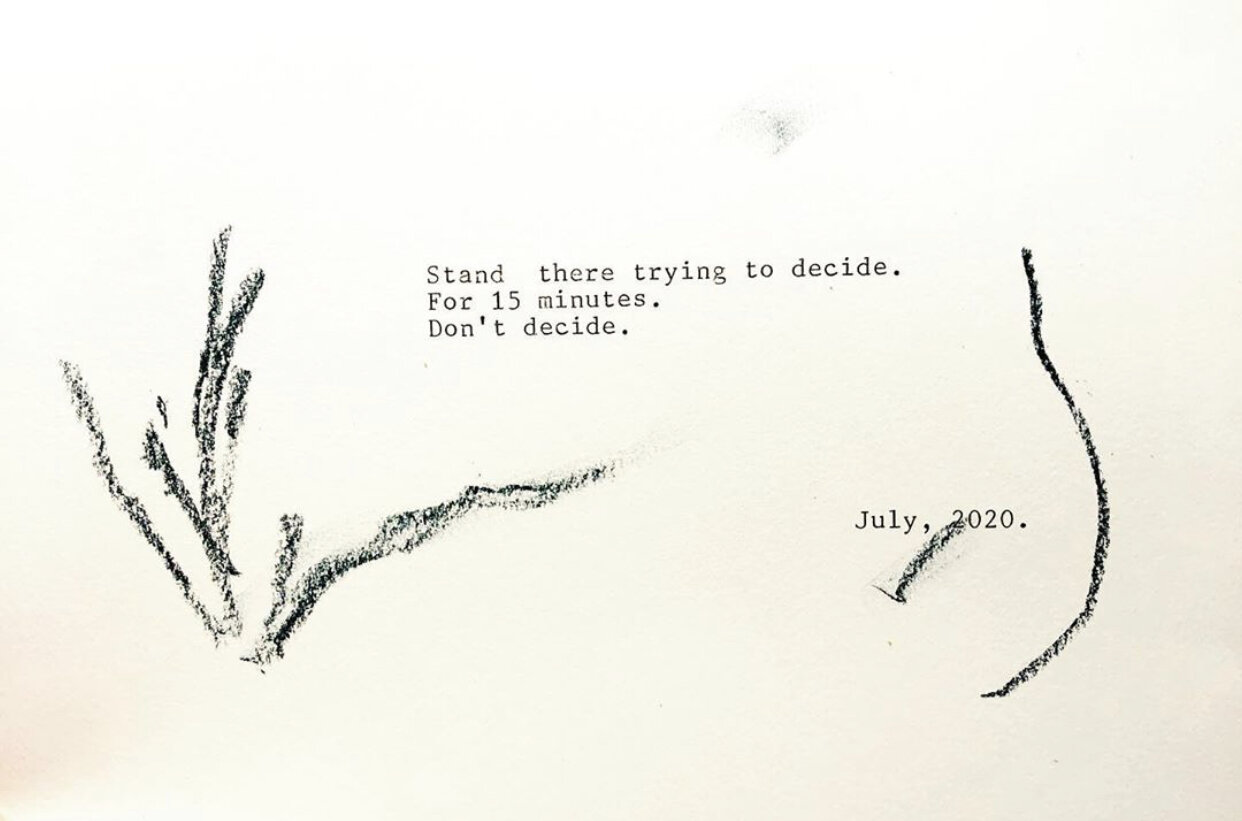

Simultaneous with the playful poetic impulses of Adam’s expression in language, he is involved in creating “walking algo-rhythms” - a fluxus-like mode for thinking about moving in the neurodivergent city that is already there - a movement that saturates his way of not only “languaging autism” and the world, but an invitation for us to attune to the world that is otherwise subtracted and ignored in the quest for fast-paced, efficient movement and “functionality” for production. The neurodivergent city that is already here. The typed text derived from experimentation on a typewriter which I write about in the dissertation - an experiment with hesitating movement, mistakes, slanting as Adam writes about ticcing, hesitation and paused movement as part of his own typing experience and language-making. The marks made in charcoal have long been with me, marks as movement of thought, also from my Relationshapes series that thought about not the why of movement with Adam, but the how - affective cartographies for thinking about movement and relation.

So much collaboration, sharing, blur. As Adam shares so much of himself, of his way of moving in the world, his way of thinking about the environment as support, his way of feeling and “seeing,” and with my time spent “mutlitasking” as artist, scholar, mother, facilitator, I attempt to manifest this step in our process with recipes for the open as yet one more movement for anyone to use, and participate. Forthcoming: Adam’s own set of poetic walking algo-rhythms. Creative synergies working together. All of our work is processual and experimental; it is never finished. This is, rather, the way we think and live together. The work we make is never the art itself but a process of thinking and moving toward the conditions that support neurodiversity. This is not art as object but art to think about neurodiverse ways of living. Adam’s lexicon emerges, with ways and paces as his, our, interest, gesturing and inviting many ways to move, perceive, live. The ways that Adam has moved my thinking and feeling, my attunement, to think poetically - in many ways - and above all, open. We might experiment with this as a neurofluxbox of objects and ideas that others can play and experiment with, to open to the neurodivergent city that is already there - a project in collaboration also with Ellen Bleiwas, Jessa Polson and Chris Martin. Or perhaps it will emerge in another form. Already brewing are poetic anti-directions and zoom calls we share walking experiences together. Let me just say that neuro is never used here in the neuroreductionist sense, but moves with the neurodiverse notion that our bodyminds are diverse among humans - that there are many ways to perceive and express in the world beyond neurotypical imaginings that confine our thinking and making. There are many ways to be, share and collaborate together. This is a new way of thinking about mutual support and care.

References:

Erin Manning. For A Pragmatics of the Useless. Duke University Press, 2020.

Adam Wolfond. In Way of Music Water Answers Toward Questions Other Than What Is Autism. Unrestricted Editions. 2019.